Sometimes in S&C programs it’s useful and applicable to have mechanisms built in to your programming to ensure athletes are progressing at an appropriate rate. By doing so you are providing a safe training environment and ensuring that athletes are not increasing loading over-aggressively, or setting themselves up for failure, or worse – injury!

If progress is the goal, why would we want to slow down the rate of progress?

Well at the beginner/novice level of strength training, athletes will adapt very quickly to training. This is because of a low training age and low exposure to the adaptations. This is one of the benefits of being a beginner – anything works at the beginning and they adapt session to session. This is also why many research studies aren’t very useful – they use beginners! As training age increases, more complex planning is required. So, really you want to try and keep your athletes in this beginner stage of adaptation for as long as possible before they hit a plateau.

So why use a jackhammer if a rubber mallet will do the job? If 5kg constitutes an increase that will stimulate adaptation, why use 15kg? Many coaches ramp up loading too quickly, simply because they can! But this is actually counter-productive in the long run as it means the youth athlete and program plateaus sooner, require more intense training, which requires greater periods of recovery. Rapidly ramping up the weight is simply a race into a roadblock… slow and steady progress is more desirable in novice trainers.

Secondly, youth athletes seldom know what an appropriate weight is that will ensure exercise technique is maintained and the desired movement qualities are reinforced. This is simply due to lack of experience and understanding. This is particularly an issue when coaching a head-strong ego oriented youth athlete, who has the tendency to chase after a numbers at the expense of movement quality (Often pushed on by over-bearing parents I might add!). Any coach who has coached youth rugby players can tell you that your back doesn’t need to be turned for long before the weights get chucked on rapidly!

So, how can you outsmart athletes hellbent on chasing numbers at the expense of quality?

- Rate limiting

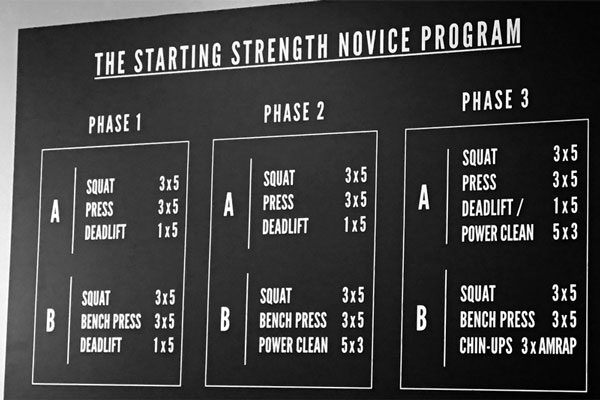

A great example of this is the “Starting Strength” novice program by Mark Rippetoe. This program is designed to be completed 3 times per week and consists of 4 compound movements: Squat, Bench/Overhead press (alternating) and Deadlift for sets of 5 reps. However, the rate of progress of loading session to session is limited as follows:

- Squat – 10lbs/4.5kg (I round to 5kg)

- Deadlift -20lbs/9kg ( I round to 10kg)

- Bench – 5lbs/2.2kg (I round to 2.5kg)

- Press – 5lbs/2.2kg (I round to 2.5kg)

Once progress begins to slow, these weight increases are then halved. This rate limiting is a pretty smart move for numerous reasons: it puts the focus on technique for a long period at first, it sets parameters to allow increases but not by inappropriate jumps, it lengthens the period of adaptation, it allows dramatic decrements in technique due to inappropriate load to be avoided and it allows for re-correction of technique early on in the training process. Mark Rippetoe has a few variations of this program as the athlete progresses, but you get the overview of the concept of rate limitation. I think this is pretty useful and I am implementing it after the initial phase of learning the lifts, once athletes are ready to commence loading.

2. Exercise Selection

This one is pretty straight forward. It’s obvious that it’s easier to produce force in bilateral barbell movements compared to dumbbell or single limb movements. For example, a barbell bench press of 100kg is significantly easier than a Dumbbell Bench Press of 50kg each. This is due to the additional stability requirement of two implements vs one solid barbell. (NOTE: I’m not advocating the use of swiss balls/Bosus in this context). The unilateral versions of exercises are great ways of putting the skids on athletes who are tempted to shoot the load up over and above their capability.

Here are some examples of variations you can use to refocus on movement over load:

- Barbell Bench Press > DB Bench > Single Arm DB Bench

- Barbell Military Press > DB Overhead Press > Single Arm DB Overhead Press

- Deadlift > DB Deadlift > Single Leg Barbell RDL > Single Leg DB RDL

- Barbell Back Squat > Barbell Split Squat > DB Split Squat > Single Leg Squat

- Barbell Back Squat > Barbell Overhead Squat

Simply swapping the compound barbell movements for one of these variations is an effective way of putting the reigns of over-enthusiastic athletes!

3. Tempo

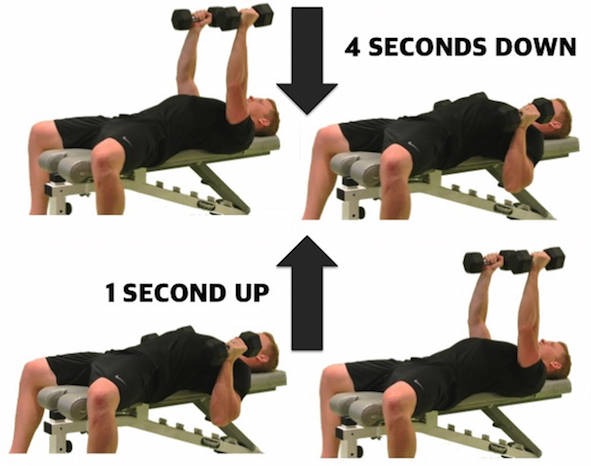

If you’ve ever utilised tempo work in your resistance training then you know how effective this can be! Simply by lengthening out the amount of time a rep is performed for increases the “time under tension” and the difficulty of the exercise. This is something that is highlighted in “Triphasic Training” by Cal Dietz.

A conventional exercise consists of 3 muscular contractions: the eccentric or lengthening phase, the isometric/amortisation or pausing/redirecting phase and the concentric or shortening phase. For example, in a squat you lower the weight (eccentric), there is a short moment where you are neither lowering nor lifting (isometric/amortisation), then there is the lifting or concentric phase.

By putting constraints on the tempo you can increase the level of control required in the movement and reduce the load able to be shifted. It’s particularly useful to lengthen the eccentric/lower phase to last 3-5 seconds, or the isometric phase (using a pause) at the bottom of the movement for 2-3 seconds. This is particularly useful pausing at the bottom of a squat or benchpress, or a few inches after the start of the deadlift. Using either of these tempo methods results in a dramatically reduced ability to shift high loads, as well as a tendency to improve technique. It also gives more time to coach a youth athlete as they are performing the exercise for longer as explained here.

I’ve been using this method pretty successfully in the initial learning phase when coaching new novice athletes. I’ve found it really useful to implement both eccentric and isometric tempo in improving technical competency in exercises.

So, if you’re struggling to keep control of head-strong athletes who are intent on lifting heavier than their ability, I hope these 3 methods will give you strategies to regain control in the weight room and assist you in getting athletes to refocus on technique over absolute load!

If you’ve found this article helpful, please share it. You can also follow us on Facebook or subscribe to our mailing list for more articles in the future!

Are you a grassroots youth sport coach or PE teacher who wants to improve the athleticism of your athletes?? Check out our Fundamental series athletic development programs here.

One thought on “What to do when loading goes too far: regaining control in the weight room…”

Comments are closed.